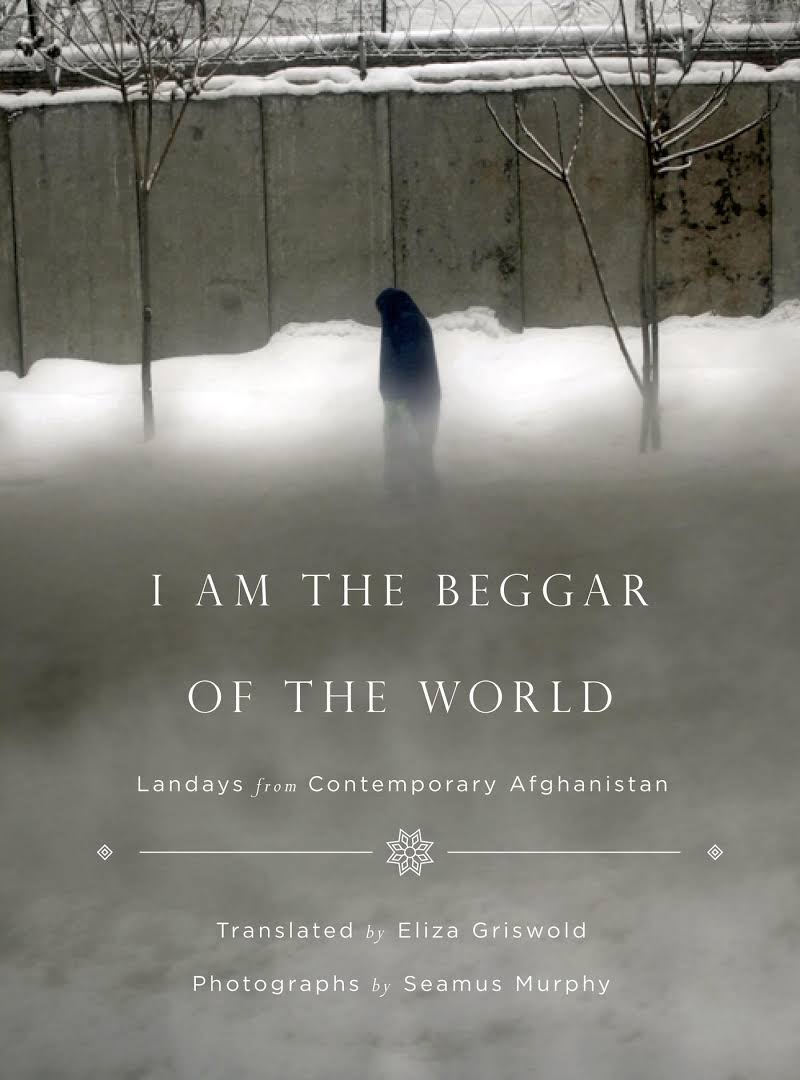

I AM THE BEGGAR OF THE WORLD: A book of poetry and photos

Excerpt taken from Poetry Magazine

I call. You’re stone. One day you'll look and find I'm gone.

The teenage poet who uttered this folk poem called herself Rahila Muska. She lived in Helmand, a Taliban stronghold and one of the most restive of Afghanistan’s thirty-four provinces since the U.S. invasion began on October 7, 2001. Muska, like many young and rural Afghan women, wasn’t allowed to leave her home. Fearing that she’d be kidnapped or raped by warlords, her father pulled her out of school after the fifth grade. Poetry, which she learned from other women and on the radio, became her only form of education.

In Afghan culture, poetry is revered, particularly the high literary forms that derive from Persian or Arabic. But the poem above is a folk couplet — a landay — an oral and often anonymous scrap of song created by and for mostly illiterate people: the more than twenty million Pashtun women who span the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Traditionally, landays are sung aloud, often to the beat of a hand drum, which, along with other kinds of music, was banned by the Taliban from 1996 to 2001, and in some places, still is.

A landay has only a few formal properties. Each has twenty-two syllables: nine in the first line, thirteen in the second. The poem ends with the sound “ma” or “na.” Sometimes they rhyme, but more often not. In Pashto, they lilt internally from word to word in a kind of two-line lullaby that belies the sharpness of their content, which is distinctive not only for its beauty, bawdiness, and wit, but also for the piercing ability to articulate a common truth about war, separation, homeland, grief, or love. Within these five main tropes, the couplets express a collective fury, a lament, an earthy joke, a love of home, a longing for the end of separation, a call to arms, all of which frustrate any facile image of a Pashtun woman as nothing but a mute ghost beneath a blue burqa.

From the Aryan caravans that likely brought these poems to Afghanistan thousands of years ago to ongoing U.S. drone strikes, the subjects of landays are remixed like hip-hop, with old words swapped for newer, more relevant ones. A woman’s sleeve in a centuries-old landay becomes her bra strap today. A colonial British officer becomes a contemporary American soldier. A book becomes a gun. Each biting word change has much to teach about the social satire that ripples under the surface of a woman’s life. With the drawdown of American forces in 2014 looming, these are the voices of protest most at risk when the Americans pull out. Although some landays reflect fury at the presence of the U.S. military, many women fear that in the absence of America’s involvement they will return to lives of isolation and oppression, just as under the Taliban.

The full article in Poetry Magazine contains insightful details about cited landaysjuxtaposed against photos by photographer Seamus Murphy.

I AM THE BEGGAR OF THE WORLD can be purchased on Amazon.